HOW TO INVESTING IN US STOCKS

The Complete Guide to Investing in US Stocks: From First Dollar to Financial Freedom

Introduction: Your Journey into the World’s Largest Wealth-Creation Machine

Welcome. You stand at the precipice of a journey that has, for over a century, been one of the most reliable paths to building significant wealth: investing in the United States stock market. This is not a get-rich-quick scheme; it is a discipline, a strategy, and a long-term partnership with the engine of global innovation and commerce.

The US stock market is more than just a collection of tickers and flashing numbers on a screen. It represents ownership in thousands of companies, from the colossal titans that shape our daily lives—Apple, Microsoft, Amazon—to the nimble, innovative startups poised to become the giants of tomorrow. When you buy a stock, you are not merely gambling on a price movement; you are purchasing a fractional stake in a real business, with its factories, its patents, its employees, and its potential for future profits.

The idea of investing can be intimidating. The language is filled with jargon (EBITDA, P/E ratios, alpha, beta), and the news is often a cacophony of fear and greed. The purpose of this guide is to demystify this world. We will cut through the noise, translate the jargon, and provide you with a robust framework for investing intelligently and confidently.

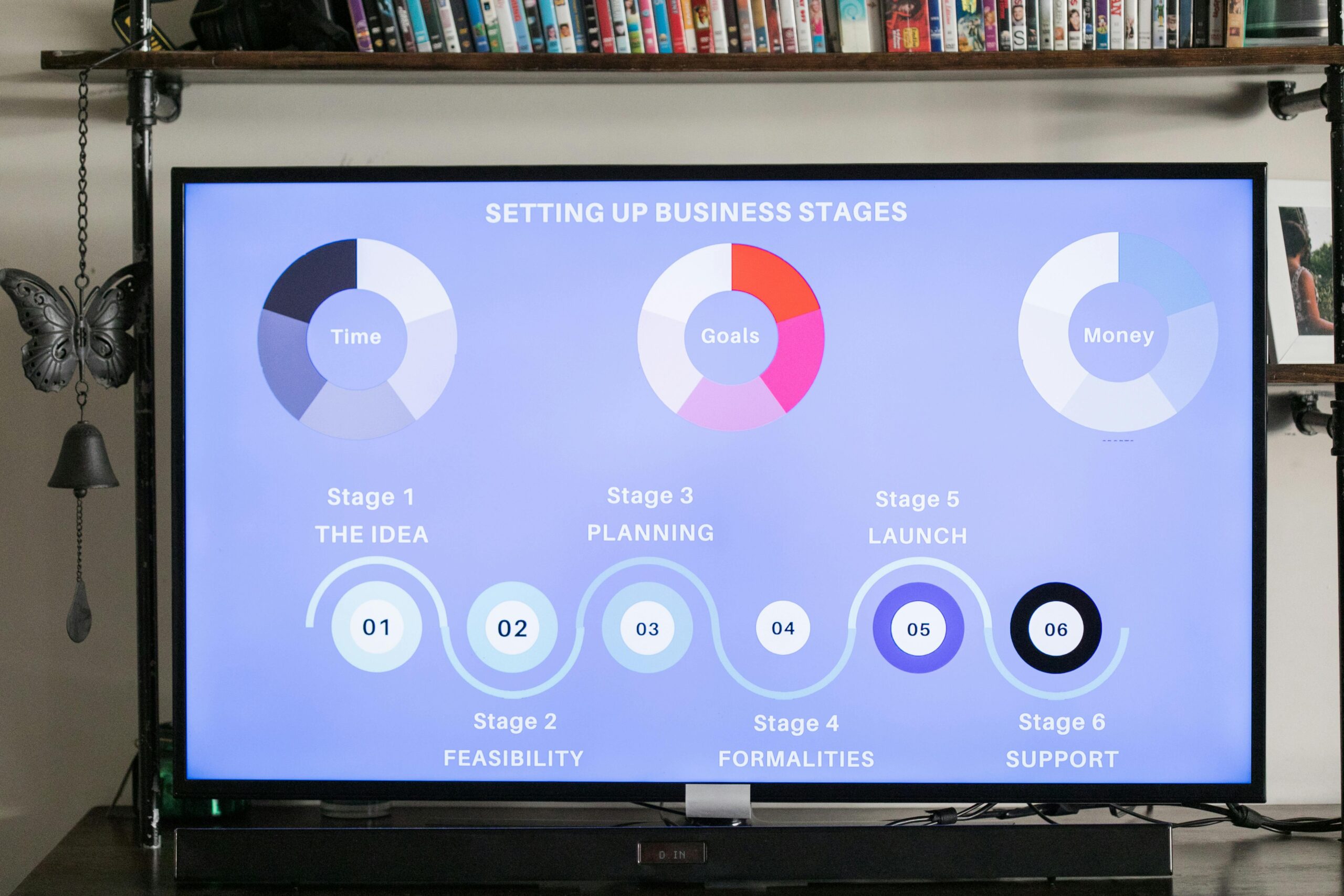

This guide is structured to take you from a complete novice to a knowledgeable investor. We will cover:

- The absolute basics: What is a stock? How does the market work?

- The practical steps: How to open an account, choose a broker, and place your first trade.

- The core philosophies: Understanding different investment strategies like value, growth, and index investing.

- The analytical tools: How to research a company and read its financial statements.

- The art of portfolio management: How to build, manage, and protect your investments over time.

- Advanced topics: Navigating taxes, market crashes, and the psychology of investing.

A 100,000-word request signifies a desire for depth, and that is what you will receive. This is your textbook, your reference manual, and your strategic guide. The journey to financial independence is a marathon, not a sprint. Let’s take the first step.

Part I: The Foundations of the Market

Before you invest a single dollar, you must understand the bedrock concepts of the market. This part builds your foundational knowledge, ensuring you know the “what” and “why” before you learn the “how.”

Chapter 1: What is a Stock? An Owner’s Mentality

At its core, a stock (also known as “equity” or a “share”) represents a slice of ownership in a publicly-traded company.

Imagine a local pizza parlor, “Luigi’s Pizza,” that is doing incredibly well. Luigi wants to expand by opening ten new locations, but he needs $1,000,000 to do it. He doesn’t have the cash, and the bank loan is too expensive. He decides to “go public” by dividing his company into 100,000 identical pieces, or shares. He then sells 50,000 of those shares to the public for $20 each, raising the $1,000,000 he needs. He keeps the other 50,000 shares, retaining 50% ownership.

If you buy 100 shares of Luigi’s Pizza, you now own 0.1% of the company. You are a part-owner. You have a claim on the company’s assets and, more importantly, its future profits.

- Why would a company issue stock? To raise capital for growth, research, acquisitions, or paying down debt without taking on interest payments.

- Why would an investor buy stock? For two primary reasons:

- Capital Appreciation: If Luigi’s expansion is successful and profits soar, the value of the entire company increases. Your 100 shares, which you bought for

2,000(2,000(20/share), might now be worth4,000(4,000(40/share). You’ve doubled your investment. - Dividends: As a part-owner, the company may choose to distribute a portion of its profits directly to you. This payment is called a dividend. If Luigi’s Pizza decides to pay a dividend of $1 per share, you would receive $100 in cash.

- Capital Appreciation: If Luigi’s expansion is successful and profits soar, the value of the entire company increases. Your 100 shares, which you bought for

Public vs. Private Companies:

Most businesses in the world are private. Your local coffee shop, dentist, and mechanic are likely private companies. They are owned by a small group of people, and their shares are not available for purchase on a public exchange.

A public company is one that has completed an Initial Public Offering (IPO), the process Luigi went through. By selling shares to the public, they agree to follow strict regulations set by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), including transparently reporting their financial results every quarter. This transparency is what allows millions of investors to analyze and value the company.

Common vs. Preferred Stock:

Most investors buy common stock. This grants you voting rights (e.g., the right to vote for the board of directors) and the potential for unlimited capital appreciation. Preferred stock is a different beast. It typically has no voting rights but pays a fixed, regular dividend. Preferred stockholders also have a higher claim on assets than common stockholders if the company goes bankrupt. For most individual investors, common stock is the primary vehicle for wealth creation.

The Mindset Shift: From this moment on, stop thinking of stocks as lottery tickets. Start thinking of them as what they are: businesses. Your goal is not to guess which ticker will go up; it is to identify and own pieces of high-quality businesses that you believe will be more valuable in the future.

Chapter 2: The US Stock Market Ecosystem

The “stock market” isn’t a single physical place. It’s a vast, interconnected network of exchanges and institutions that facilitate the buying and selling of stocks.

The Major Exchanges:

These are the marketplaces where stocks are traded.

- The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE): Founded in 1792, the NYSE is the iconic symbol of American capitalism. It’s an auction market, where human brokers (along with electronic systems) match buyers and sellers. It is home to many of the world’s largest, most established “blue-chip” companies like Johnson & Johnson, Coca-Cola, and JPMorgan Chase.

- The Nasdaq Stock Market: Founded in 1971, the Nasdaq is a dealer’s market and was the world’s first electronic stock exchange. It operates entirely through a network of computers. It is famous for being the home of technology and innovation, listing giants like Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google (Alphabet), and Meta Platforms (Facebook).

When a company is listed on an exchange like the NYSE or Nasdaq, it means its shares are available for trading there.

Market Indexes: The Market’s Barometer

It’s impossible to track the performance of all 6,000+ stocks in the US. Instead, we use market indexes, which are curated baskets of stocks that represent a portion of the market. They are the benchmarks against which we measure performance.

- The S&P 500 (Standard & Poor’s 500): This is the most widely followed index. It includes 500 of the largest and most influential public companies in the US. It’s considered the best single gauge of the large-cap US stock market. When you hear “the market was up today,” people are usually referring to the S&P 500.

- The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA): Often just called “the Dow,” this is the oldest and most famous index. It tracks just 30 large, well-known blue-chip companies. Because it’s so small and its calculation method (price-weighted) is quirky, most professionals prefer the S&P 500, but the Dow still holds significant historical and media importance.

- The Nasdaq Composite Index: This index tracks all of the thousands of stocks listed on the Nasdaq exchange. It is heavily weighted towards technology stocks, so its performance often reflects the health of the tech sector.

Key Players in the Ecosystem:

- You, the Investor: The individual (retail) or institution (pension fund, hedge fund) providing the capital.

- Brokerage Firms (Brokers): Your gateway to the market. These are the companies (like Fidelity, Charles Schwab, Vanguard, Robinhood) that hold your money and execute your buy and sell orders on the exchanges. You cannot trade directly on the NYSE or Nasdaq; you must go through a broker.

- The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC): The government’s watchdog. The SEC’s mission is to protect investors, maintain fair and orderly markets, and facilitate capital formation. They enforce the rules, combat fraud, and require companies to disclose their financial information.

- Market Makers: These are firms that stand ready to buy or sell a particular stock at any given time, providing liquidity to the market. They make money on the “bid-ask spread”—the tiny difference between the price at which they’re willing to buy (bid) and sell (ask).

Chapter 3: Why Invest in US Stocks?

With global markets available, why is there such a strong focus on the US?

- Historical Performance and Growth: Over the long run, the US stock market has delivered powerful returns. Since 1926, the S&P 500 has averaged an annual return of around 10%. This rate of return, supercharged by the power of compounding, has a staggering ability to grow wealth over time.

- Global Leadership and Innovation: The US is home to the world’s most dominant and innovative companies. From technology and healthcare to finance and consumer goods, US firms are often at the forefront of global trends. Investing in the US market gives you a stake in this engine of innovation.

- Liquidity and Transparency: The US markets are the deepest and most liquid in the world. “Liquidity” means you can buy or sell stocks quickly without dramatically affecting the price. The strict SEC reporting requirements also mean that US markets are among the most transparent, providing investors with a wealth of reliable data.

- The US Dollar as the World’s Reserve Currency: The global economy runs on the US dollar. This provides a level of stability and reduces currency risk for those who live and spend in dollars.

- Shareholder-Friendly Culture: US corporate culture is generally focused on maximizing shareholder value. This means companies are often incentivized to grow profits, innovate, and return capital to shareholders through dividends and stock buybacks.

Chapter 4: A Glossary of Core Concepts & Terminology

Let’s define some essential terms you’ll encounter daily.

- Bull Market 🐂 vs. Bear Market 🐻:

- A Bull Market is a period of generally rising stock prices and investor optimism. The term is typically used when a major index, like the S&P 500, rises 20% or more from a recent low.

- A Bear Market is the opposite: a period of falling prices and pessimism. It’s defined as a market decline of 20% or more from a recent high. Bear markets are a normal, albeit painful, part of the investing cycle.

- Market Capitalization (Market Cap): This is the total value of a company’s shares. It’s calculated by: Share Price × Number of Shares Outstanding. Market cap is the primary way we categorize company size:

- Large-Cap (Mega-Cap): >$10 billion (e.g., Apple, Microsoft). Stable, established leaders.

- Mid-Cap: $2 billion to $10 billion. A blend of the stability of large-caps and the growth potential of small-caps.

- Small-Cap: <$2 billion. Higher risk, but higher potential for rapid growth.

- Volatility: A measure of how much a stock’s price swings up and down. A highly volatile stock (like a young biotech company) will have wild price movements, while a low-volatility stock (like a utility company) will have a steadier price.

- Dividend: The portion of a company’s profit paid out to shareholders, typically quarterly. The Dividend Yield is the annual dividend per share divided by the stock’s current price, expressed as a percentage.

- Stock Buyback (Share Repurchase): When a company uses its cash to buy its own shares from the open market. This reduces the number of shares outstanding, which increases the ownership percentage of the remaining shareholders and tends to boost the earnings per share (EPS).

- Earnings Per Share (EPS): A company’s total profit divided by the number of shares outstanding. It’s a key indicator of profitability.

- Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio: One of the most common valuation metrics. It’s calculated by: Stock Price ÷ Earnings Per Share. A high P/E ratio can suggest that a stock is expensive or that investors expect high future growth. A low P/E ratio can suggest a stock is cheap or that the company faces challenges.

- Ticker Symbol: The unique one-to-five-letter code used to identify a stock on an exchange (e.g., AAPL for Apple, JNJ for Johnson & Johnson).

Part II: Getting Started – Your First Steps as an Investor

Theory is important, but a journey requires action. This part covers the practical, step-by-step process of becoming an investor.

Chapter 5: Your Pre-Investment Financial Checklist

Investing is not the first step in a financial plan; it’s the third or fourth. Before you invest in the stock market, you must build a stable financial foundation. Otherwise, you risk having to sell your investments at the worst possible time (e.g., during a market downturn) to cover an emergency.

1. Create a Budget and Track Your Spending: You cannot invest money you don’t have. Understand where your money is going and identify surplus cash that can be dedicated to investing.

2. Eliminate High-Interest Debt: This is non-negotiable. If you have credit card debt at 22% interest, paying that off provides a guaranteed, risk-free 22% return. No investment in the stock market can promise that. Prioritize paying off any debt with an interest rate above 6-7%. Low-interest debt like a mortgage is generally acceptable to carry while investing.

3. Build an Emergency Fund: This is your financial firewall. Your emergency fund should contain 3 to 6 months’ worth of essential living expenses (rent/mortgage, food, utilities, insurance). This money should be kept in a highly liquid, safe account, like a high-yield savings account—NOT in the stock market. This fund protects you from life’s surprises (job loss, medical emergency) and prevents you from becoming a forced seller of your investments.

4. Define Your Financial Goals and Time Horizon: Why are you investing? The answer dictates your strategy.

- Retirement (20+ years away): You have a long time horizon, so you can afford to take more risk for higher potential returns.

- A House Down Payment (5-7 years away): A medium time horizon. Your portfolio should be more balanced between stocks and less volatile assets like bonds.

- A Car Purchase (1-2 years away): A short time horizon. This money should not be in the stock market. The risk of a market decline right before you need the cash is too high.

5. Assess Your Risk Tolerance: How would you feel if your portfolio dropped 30% in a month?

- Aggressive: You’re comfortable with high volatility for the chance at maximum long-term growth. Your portfolio will be heavily weighted towards stocks.

- Moderate: You want growth but are also concerned with preserving capital. You’ll have a balanced mix of stocks and bonds.

- Conservative: Your primary goal is to protect your principal. You can’t stomach large drawdowns. Your portfolio will be weighted towards bonds and dividend-paying stocks.

Be honest with yourself. Mismatching your portfolio with your true risk tolerance is a recipe for panic-selling.

Chapter 6: Choosing a Brokerage Account

Your broker is your partner in investing. Choosing the right one is crucial. Today, for most individual investors, a discount brokerage firm is the best choice. These firms offer low (or zero) commission trades and provide robust online platforms and mobile apps.

Key Features to Compare in a Broker:

- Commissions and Fees: The good news is that most major US brokers (Fidelity, Schwab, Vanguard, E*TRADE) now offer $0 commission trades for stocks and ETFs. However, be aware of other fees: account maintenance fees, inactivity fees, and fees for trading mutual funds or options.

- Account Types: Ensure the broker offers the accounts you need. The three main types are:

- Taxable Brokerage Account: The standard account. No contribution limits. You pay taxes on dividends and capital gains in the year they are realized.

- Traditional IRA (Individual Retirement Account): A tax-deferred retirement account. Contributions may be tax-deductible now, and the money grows tax-free. You pay income tax on withdrawals in retirement.

- Roth IRA: A tax-advantaged retirement account. Contributions are made with after-tax dollars (no deduction now). The money grows completely tax-free, and qualified withdrawals in retirement are 100% tax-free. For most young and middle-income investors, the Roth IRA is an incredibly powerful tool.

(Note: IRAs have annual contribution limits set by the government.)

- Investment Selection: Do they offer a wide range of stocks, ETFs, and mutual funds? Do they offer fractional shares? Fractional shares allow you to invest a specific dollar amount (e.g.,

50)inastock,evenifonesharecostsmore(likeAmazonat 50)inastock,evenifonesharecostsmore(likeAmazonat3,000). This is a fantastic feature for new investors. - Platform and Tools: Is the website/app easy to use? Do they offer good research tools, stock screeners, and educational resources?

- Customer Service: Can you easily reach a human for help when you need it?

Top Broker Recommendations for Most Investors:

- Fidelity: Often considered the best all-around broker. $0 commissions, excellent platform, fractional shares, top-tier customer service, and strong fund offerings.

- Charles Schwab: Another industry giant with a fantastic reputation. Very similar to Fidelity in its offerings. (Schwab has since acquired TD Ameritrade, integrating its excellent thinkorswim platform for active traders).

- Vanguard: The pioneer of low-cost index investing. The platform is a bit more basic, but it is owned by its funds, giving it a unique client-aligned structure. Ideal for long-term, passive investors who primarily use Vanguard’s own ETFs and mutual funds.

Chapter 7: Opening and Funding Your Account

This process is straightforward and similar to opening a bank account.

- Choose your broker.

- Go to their website and click “Open an Account.”

- Select the account type (Taxable, Roth IRA, etc.).

- Provide your personal information: Name, address, date of birth, and Social Security Number (or equivalent for international investors). You’ll also be asked about your employment status and basic financial information (income, net worth). This is required by regulators.

- Fund the account. You can link your bank account and transfer money electronically (ACH transfer), which is usually free and takes 1-3 business days. You can also wire money or mail a check.

Congratulations! Once the money clears, you are ready to invest.

Chapter 8: The Main Investment Vehicles: Stocks, ETFs, and Mutual Funds

You don’t just have to buy individual stocks. You can also buy funds that hold hundreds or thousands of stocks at once.

| Feature | Individual Stocks | Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) | Mutual Funds |

| What You Own | A direct stake in one company. | A basket of stocks (or bonds) that trades like a single stock on an exchange. | A professionally managed portfolio of stocks (or bonds). |

| Diversification | Low (you must buy many stocks to diversify). | High (one share can give you exposure to the entire S&P 500). | High (one share gives you exposure to the entire fund portfolio). |

| How it Trades | Throughout the day, prices change constantly. | Throughout the day, like a stock. | Price is set only once per day, after the market closes. |

| Cost (Expense Ratio) | None (besides trade commission, if any). | Generally very low, especially for index ETFs (e.g., 0.03%). | Varies wildly. Index funds are cheap, but actively managed funds can be expensive (1%+). |

| Best For | Investors who enjoy deep research and want to own specific companies. | Almost everyone. The best tool for instant, low-cost diversification. | Investors who want a hands-off approach and believe a professional manager can beat the market. |

Deep Dive into ETFs:

ETFs are arguably the greatest financial innovation for individual investors in the last 50 years. They offer the diversification of a mutual fund with the trading flexibility and low costs of a stock.

- Index ETFs: These are the most popular type. They don’t try to beat the market; they aim to be the market. They passively track an index.

- SPY (SPDR S&P 500 ETF): Tracks the S&P 500.

- VTI (Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF): Tracks the entire US stock market, including large, mid, and small-cap stocks.

- QQQ (Invesco QQQ Trust): Tracks the Nasdaq 100 index (the 100 largest non-financial companies on the Nasdaq).

- Sector ETFs: These focus on a specific industry, like technology (XLK), healthcare (XLV), or finance (XLF).

- Thematic ETFs: These focus on a specific trend, like robotics (BOTZ) or clean energy (ICLN). Use with caution, as these can be more speculative.

For 90% of investors, a core holding of a broad-market index ETF like VTI or SPY is the most sensible, effective, and low-cost way to invest in the US stock market.

Chapter 9: Placing Your First Trade – The Mechanics

You’ve done the prep work, opened your account, and chosen what you want to buy. Here’s how to execute the trade on your broker’s platform.

- Log in and navigate to the “Trade” screen.

- Enter the Ticker Symbol of the stock or ETF you want to buy (e.g., “AAPL” for Apple).

- Select the Action: “Buy” or “Sell.”

- Enter the Quantity: Either the number of shares or the dollar amount (if using fractional shares).

- Choose the Order Type: This is a crucial step.

- Market Order: This is the simplest order. It tells your broker to buy or sell the stock immediately at the best available current price. Warning: The price can change in the split second it takes to execute the trade. For a liquid stock like Apple, this difference is negligible. For a volatile, thinly traded stock, you could get a much worse price than you expected. Use with caution.

- Limit Order: This is the recommended order type for most investors. It allows you to set the maximum price you are willing to pay for a stock (a “buy limit”) or the minimum price you are willing to accept to sell it (a “sell limit”). For example, if AAPL is trading at $175.50, you could set a buy limit order at $175.00. Your order will only execute if the price drops to $175.00 or lower. This protects you from paying more than you’re comfortable with.

- Stop-Loss Order (or Stop Order): This is a risk management tool. It’s an order to sell a stock if its price falls to a certain level, limiting your potential losses. For example, if you bought a stock at $50, you might set a stop-loss at $45. If the price drops to $45, your stop-loss order becomes a market order to sell.

For your first purchase, a buy limit order set at or slightly above the current asking price is often the safest and most controlled way to enter a position.

- Review and Confirm. Double-check everything: ticker, action, quantity, order type. Then, click “Place Order.”

You did it. You are now an investor and a part-owner of a business.

Part III: Investment Strategies & Philosophies

There is more than one way to succeed in investing. Your personality, goals, and interest level will determine which philosophy suits you best. This part explores the great debates and proven strategies that have guided investors for decades.

Chapter 10: The Great Debate: Passive vs. Active Investing

This is the central philosophical divide in the investment world.

Active Investing:

- The Goal: To “beat the market.” Active investors (or active fund managers) believe that through superior research, analysis, and timing, they can achieve returns that outperform a benchmark index like the S&P 500.

- The Method: Involves frequent buying and selling, in-depth company analysis, and making strategic bets on specific stocks, sectors, or market trends. Stock picking is an active strategy.

- The Pros: The potential for massive outperformance (think of Peter Lynch’s legendary run at the Magellan Fund). It’s intellectually stimulating and engaging.

- The Cons: It’s extremely difficult. Decades of data show that the vast majority of professional active managers fail to beat their benchmark index over the long term, especially after accounting for their higher fees and trading costs. It’s also time-consuming and can be emotionally taxing.

Passive Investing:

- The Goal: To “be the market.” Passive investors don’t try to find the needle in the haystack; they buy the entire haystack. They aim to match the return of a market index, minus a tiny fee.

- The Method: Buying and holding a low-cost, broad-market index fund or ETF (like VTI or SPY). There is no stock picking or market timing. It’s a “set it and forget it” approach.

- The Pros: It’s simple, low-cost, and highly effective. It guarantees you will capture the market’s return. It removes emotion from the equation and requires very little time. It consistently outperforms most active investors over the long haul.

- The Cons: You will never beat the market; you are the market. You will experience every bit of the market’s downturns. It can feel boring to those who crave action.

The Verdict for Most Investors: A core portfolio built on passive index funds is the most reliable path to wealth creation. You can then, if you wish, use a smaller “satellite” portion of your portfolio (5-10%) for active stock picking if you enjoy the research and are willing to take the risk.

Chapter 11: Value Investing – Buying Dollars for 50 Cents

- The Philosophy: Popularized by Benjamin Graham and perfected by his student, Warren Buffett, value investing is the art of buying stocks for less than their calculated intrinsic value. Value investors are bargain hunters. They believe the market is often emotional and irrational, creating opportunities to buy great companies at a discount.

- The Metaphor: Buffett’s “Mr. Market.” Imagine you have a business partner, Mr. Market, who is manic-depressive. Every day, he offers to sell you his shares or buy yours at a different price. Some days he’s euphoric and quotes a ridiculously high price. Other days he’s despondent and offers to sell you his shares for far less than they’re worth. A value investor ignores him on his euphoric days and happily buys from him on his despondent days.

- Key Concepts:

- Intrinsic Value: The “true” underlying value of a business, based on its assets, earnings power, and future prospects. This is an estimate, not a precise number.

- Margin of Safety: The cornerstone of value investing. You only buy a stock when its market price is significantly below your estimate of its intrinsic value. If you believe a company is worth $100 per share, you might only be willing to buy it at $70 or less. This discount provides a buffer against errors in judgment or bad luck.

- What Value Investors Look For:

- Low P/E ratios (compared to the industry or market).

- Low Price-to-Book (P/B) ratios.

- Strong balance sheets with low debt.

- Consistent, predictable earnings.

- Durable competitive advantages (a “moat”).

Chapter 12: Growth Investing – Riding the Wave of Innovation

- The Philosophy: Growth investors are less concerned with a stock’s current price and more focused on its potential for rapid future growth. They seek out companies that are expanding their revenues and earnings at a much faster rate than the overall market.

- The Mindset: “The price is high, but it will be much higher in the future.” They are willing to pay a premium for companies that are leaders in high-growth industries like technology, biotech, or e-commerce. Philip Fisher and Peter Lynch are famous proponents of this style.

- What Growth Investors Look For:

- High revenue growth rates (e.g., >20% per year).

- High earnings growth rates.

- Large and growing addressable markets.

- Visionary leadership.

- Innovative products or services that are disrupting an industry.

- They are comfortable with high P/E ratios, as they believe the “E” (earnings) will grow into the “P” (price).

Chapter 13: Dividend (Income) Investing – Getting Paid to Wait

- The Philosophy: The primary goal is to build a portfolio of stocks that generate a steady and rising stream of income through dividends. Capital appreciation is a secondary goal. This strategy is popular with retirees or anyone seeking passive income.

- The Method: Focus on mature, stable companies with a long history of paying and increasing their dividends. These are often blue-chip companies in sectors like consumer staples (Procter & Gamble), healthcare (Johnson & Johnson), and utilities.

- Key Concepts:

- Dividend Aristocrats: S&P 500 companies that have increased their dividend for at least 25 consecutive years.

- DRIP (Dividend Reinvestment Plan): An option offered by most brokers to automatically use your dividend payments to buy more shares (or fractional shares) of the same stock. This is a powerful, automated way to compound your investment.

Chapter 14: Blending the Styles – The GARP Approach

Many of the most successful investors don’t fit neatly into one box. Growth at a Reasonable Price (GARP) is a hybrid strategy that combines elements of both value and growth investing.

A GARP investor looks for companies with strong growth prospects but is unwilling to pay the astronomical prices that pure growth investors might. They look for a P/E ratio that is below the company’s earnings growth rate—a metric known as the PEG ratio (Price/Earnings-to-Growth). A PEG ratio below 1.0 is often considered attractive.

Part IV: Analysis and Research – Doing Your Homework

If you choose to venture beyond index funds and pick individual stocks, you must learn how to analyze a business. This is where you become a financial detective.

Chapter 15: How to Read Financial Statements

Every public company must file its financial statements with the SEC. The most important filing is the Annual Report (Form 10-K), which contains a wealth of information. The three key financial statements are the “Big Three”:

- The Income Statement (The P&L):

- What it shows: A company’s financial performance over a period of time (a quarter or a year). It’s like a video.

- Key Line Items:

- Revenue (or Sales): The top line. The total amount of money generated from selling goods or services. Is it growing consistently?

- Cost of Goods Sold (COGS): The direct costs of producing those goods or services.

- Gross Profit: Revenue – COGS.

- Operating Expenses: Costs not directly related to production, like R&D, sales, and marketing.

- Operating Income: A key measure of core profitability before interest and taxes.

- Net Income (or “The Bottom Line”): The company’s total profit after all expenses, including interest and taxes, have been deducted. This is the “earnings” in the P/E ratio.

- The Balance Sheet:

- What it shows: A snapshot of a company’s financial position at a single point in time. It’s like a photograph.

- The Fundamental Equation: Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders’ Equity

- Key Line Items:

- Assets: What the company owns (cash, inventory, property, equipment).

- Liabilities: What the company owes (debt, accounts payable).

- Shareholders’ Equity: The net worth of the company. It’s the value that would be left over for shareholders if the company sold all its assets and paid off all its liabilities. You want to see this growing over time.

- The Cash Flow Statement:

- What it shows: How cash moves in and out of a company. Some say this is the most important statement because it’s the hardest to manipulate with accounting tricks. “Profit” is an opinion; “cash” is a fact.

- Three Sections:

- Cash Flow from Operations (CFO): Cash generated by the company’s core business activities. This should be positive and ideally growing. A healthy company’s net income should be closely matched by its CFO.

- Cash Flow from Investing (CFI): Cash used for investments, like buying new equipment (a cash outflow) or selling assets (a cash inflow).

- Cash Flow from Financing (CFF): Cash flow between the company and its owners/creditors. Issuing stock or taking on debt is a cash inflow; paying dividends or buying back stock is a cash outflow.

Chapter 16: Key Financial Ratios and Metrics

Ratios allow you to compare companies of different sizes and to analyze trends over time.

- Profitability Ratios:

- Return on Equity (ROE): Net Income / Shareholders’ Equity. Measures how efficiently a company is using its shareholders’ money to generate profit. An ROE consistently above 15% is often considered excellent.

- Gross Margin: (Gross Profit / Revenue) × 100. Shows the percentage of revenue left after accounting for the cost of goods. A high margin indicates a more profitable core business.

- Valuation Ratios:

- P/E Ratio: Price / EPS. As discussed, tells you how much you’re paying for $1 of earnings.

- Price/Sales (P/S) Ratio: Market Cap / Total Revenue. Useful for valuing companies that aren’t yet profitable (like many young tech firms).

- PEG Ratio: (P/E Ratio) / EPS Growth Rate. As discussed, a tool for GARP investors.

- Leverage (Debt) Ratios:

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio: Total Liabilities / Shareholders’ Equity. Measures how much debt a company is using to finance its assets relative to the value of its equity. A ratio below 1.0 is generally considered safe, though this varies by industry.

Important Note: Ratios are meaningless in a vacuum. You must compare them to (a) the company’s own historical numbers, (b) its direct competitors, and (c) the industry average.

Chapter 17: Qualitative Analysis – The Story Behind the Numbers

Numbers only tell part of the story. Qualitative factors are the intangible aspects of a business that are crucial for long-term success.

- Competitive Advantage (The “Moat”): Coined by Warren Buffett, a moat is a durable competitive advantage that protects a company from competitors, just as a moat protects a castle. What makes this company difficult to compete with?

- Network Effects: The service becomes more valuable as more people use it (e.g., Facebook, Visa).

- Intangible Assets: Strong brands (Coca-Cola), patents (a pharmaceutical company), or regulatory licenses.

- Cost Advantages: The ability to produce a product or service at a lower cost than rivals (e.g., Walmart’s scale, GEICO’s direct-to-consumer model).

- Switching Costs: It’s a pain for customers to switch to a competitor (e.g., your bank, Apple’s ecosystem).

- Management Quality: Is the leadership team honest, competent, and shareholder-friendly? Read their annual letters to shareholders. Do they speak in plain English or corporate jargon? Do they admit their mistakes? Do their incentives (executive compensation) align with long-term shareholder interests?

- Industry Trends: Is the company in a growing industry (a tailwind) or a dying one (a headwind)? A brilliant company in a terrible industry faces an uphill battle.

- Company Culture: Does the company have a culture of innovation and excellence that attracts and retains top talent?

Chapter 18: Where to Find Information

- Company Investor Relations (IR) Websites: The best place to start. You’ll find annual reports (10-K), quarterly reports (10-Q), investor presentations, and conference call transcripts.

- SEC’s EDGAR Database: The official repository for all public company filings.

- Financial News Websites: The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, Reuters.

- Brokerage Research: Most full-service brokers like Fidelity and Schwab provide a wealth of analyst reports and screening tools.

- Value Line, Morningstar: Subscription services that provide detailed, one-page summaries and analysis of thousands of stocks.

Part V: Portfolio Management & The Long Game

Picking a good stock is only one part of the equation. How you combine your investments into a cohesive portfolio and how you behave over time will ultimately determine your success.

Chapter 19: The Only Free Lunch: Diversification & Asset Allocation

Diversification is the practice of spreading your investments around so that your exposure to any single asset is limited. It’s the bedrock principle of risk management. The old saying, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket,” is the essence of diversification.

Asset Allocation is how you diversify. It’s the decision of how to split your portfolio among different asset classes. The three main asset classes are:

- Stocks (Equities): The engine of growth.

- Bonds (Fixed Income): The shock absorber. They tend to be less volatile than stocks and may even rise when stocks fall.

- Cash & Cash Equivalents: For safety and opportunity.

Your asset allocation is the single most important determinant of your portfolio’s returns and volatility. A common rule of thumb for a moderate portfolio is a 60/40 split (60% stocks, 40% bonds).

- An aggressive young investor might be 90% stocks, 10% bonds.

- A conservative retiree might be 30% stocks, 70% bonds.

Diversification Within Stocks:

Don’t just own one stock. Don’t even just own ten.

- Across Sectors: Own companies in technology, healthcare, financials, consumer staples, etc. If tech has a bad year, your healthcare stocks might do well.

- Across Company Sizes: Own large-cap, mid-cap, and small-cap stocks.

- Across Geographies: While this guide focuses on the US, a truly diversified portfolio includes international stocks as well (e.g., through an international index ETF like VXUS).

The easiest way to achieve instant, broad diversification is through a total market index ETF like VTI.

Chapter 20: Building and Rebalancing Your Portfolio

Once you decide on your target asset allocation (e.g., 80% stocks, 20% bonds), you need to maintain it. Over time, your allocation will drift. If stocks have a great year, your portfolio might drift to 85% stocks and 15% bonds, making it riskier than you intended.

Rebalancing is the process of periodically selling some of your winners and buying more of your underperforming assets to return to your target allocation.

- How often? Once a year is sufficient for most investors.

- The benefit: It forces you to obey the classic investing maxim: “Buy low, sell high.” It imposes discipline and prevents your portfolio’s risk profile from getting out of whack.

Chapter 21: The Psychology of Investing – Conquering Your Worst Enemy

The biggest threat to your investment returns isn’t the market, it’s you. Behavioral finance has shown that our brains are hardwired to make terrible financial decisions. Understanding these biases is the first step to overcoming them.

- Fear and Greed: These are the two primary emotions that drive the market. Greed causes investors to pile into assets at the peak of a bubble, and fear causes them to panic-sell at the bottom of a crash. The goal is to be “fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful” (Buffett).

- FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out): Watching a stock soar and feeling an irresistible urge to buy it, regardless of its price or value. This is a recipe for buying high.

- Loss Aversion: The pain of a loss is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of an equivalent gain. This causes investors to hold on to their losing stocks for too long, hoping they’ll “come back,” while selling their winners too early to lock in a small profit.

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs and to ignore information that contradicts them. If you’re bullish on a stock, you’ll gravitate towards positive news about it.

- Herding: The instinct to follow the crowd. When everyone else is selling, the pressure to sell is immense. When everyone is buying, it feels safe to join in. But the crowd is often wrong at major market turning points.

The Antidote: Have a plan and stick to it. Automate your investments. Focus on the long term. Turn off the financial news. Remember that bear markets and corrections are normal and healthy.

Chapter 22: Market Crashes & Bear Markets – A Survival Guide

They will happen. Since World War II, the S&P 500 has experienced a bear market (a drop of 20%+) roughly every 5-6 years on average. These are not a sign that the system is broken; they are a feature, not a bug. They wash out excess and create incredible buying opportunities for those with cash and courage.

Your Bear Market To-Do List:

- Do Nothing. For most people, the best course of action is to simply not look at your portfolio and stick to your long-term plan. Do not sell. Selling after a 30% drop just locks in your losses.

- Remember History. The market has always recovered from every single crash and gone on to new all-time highs. Always.

- Review Your Pre-Checklist. This is why you have an emergency fund. You won’t be a forced seller.

- If You Can, Buy More. If you are still in your earning years and have cash, a bear market is the greatest sale you’ll ever see. Systematically adding money during a downturn is how serious wealth is built.

- Rebalance. As discussed, a bear market is the perfect time to rebalance your portfolio.

Part VI: Advanced Topics & Special Considerations

Chapter 23: The Crucial Role of Taxes

Your real return is what you keep after taxes. Understanding tax rules is essential.

- Capital Gains: When you sell a stock for a profit, you have a capital gain.

- Short-Term Capital Gains: If you held the stock for one year or less. These gains are taxed at your ordinary income tax rate, which is high.

- Long-Term Capital Gains: If you held the stock for more than one year. These gains are taxed at much lower preferential rates (0%, 15%, or 20% depending on your income).

- The Takeaway: There is a huge tax incentive to be a long-term investor. Avoid frequent trading in a taxable account.

- Tax-Advantaged Accounts (IRAs, 401(k)s): Your secret weapon. Inside these retirement accounts, you can buy and sell without triggering any capital gains taxes. This allows your money to compound much faster. Max out these accounts before investing heavily in a taxable account.

- Tax-Loss Harvesting: A strategy for taxable accounts. If you have investments that have lost value, you can sell them to realize a “capital loss.” This loss can be used to offset capital gains elsewhere in your portfolio. You can also deduct up to $3,000 in net capital losses against your ordinary income each year.

(Disclaimer: I am an AI, not a tax advisor. Consult a qualified professional for advice specific to your situation.)

Chapter 24: Investing for International Residents

If you are not a US resident, you can still invest in US stocks.

- Choosing a Broker: Many US brokers (like Interactive Brokers and Charles Schwab’s international arm) accept clients from around the world. There are also many brokers in your home country that offer access to US markets.

- Form W-8BEN: This is a crucial form you will fill out for your broker. It certifies that you are not a US person and allows you to claim a reduced rate of tax on dividends, as specified by the tax treaty between your country and the US.

- Taxes: Typically, the US will withhold a tax on dividends paid to you (often 30%, but reduced to 15% or less by most tax treaties). The US generally does not tax capital gains for non-resident aliens. You will still be subject to the tax laws of your own country.

Conclusion: The Investor’s Creed

You have now journeyed from the basics of what a stock is to the complexities of portfolio theory and behavioral finance. If you remember nothing else, remember this creed:

- I am an owner, not a speculator. I invest in businesses, not tickers.

- I will save and invest consistently. The amount I save is more important than my investment returns in the early years. I will automate my investments.

- I will have a plan. I will define my goals, asset allocation, and strategy before I start, and I will stick to it.

- I will embrace the long term. I understand that wealth is built over decades, not days. I will let compounding work its magic.

- I will control what I can control. I cannot control the market’s returns, but I can control my costs, my asset allocation, my behavior, and my tax efficiency.

- I will be a lifelong learner. The world changes, and I will continue to read, learn, and adapt.

The US stock market is a powerful tool. Used with discipline, patience, and knowledge, it can help you achieve your most ambitious financial goals. The journey is long, but it is a worthy one.

Begin.

Appendix A: Recommended Reading

- For Beginners: The Simple Path to Wealth by JL Collins, The Bogleheads’ Guide to Investing by Taylor Larimore et al.

- For Value Investors: The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham (Chapters 8 & 20 are essential), The Little Book of Common Sense Investing by John C. Bogle.

- For Stock Pickers: One Up On Wall Street by Peter Lynch, Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits by Philip Fisher.

- For Psychology: The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel, Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman.

Appendix B: Useful Websites & Resources

investopedia.com: For definitions of any financial term you encounter.

sec.gov/edgar: For official company filings (10-K, 10-Q).

morningstar.com: For fund and stock analysis.

finance.yahoo.com: For free charts, news, and basic financial data.